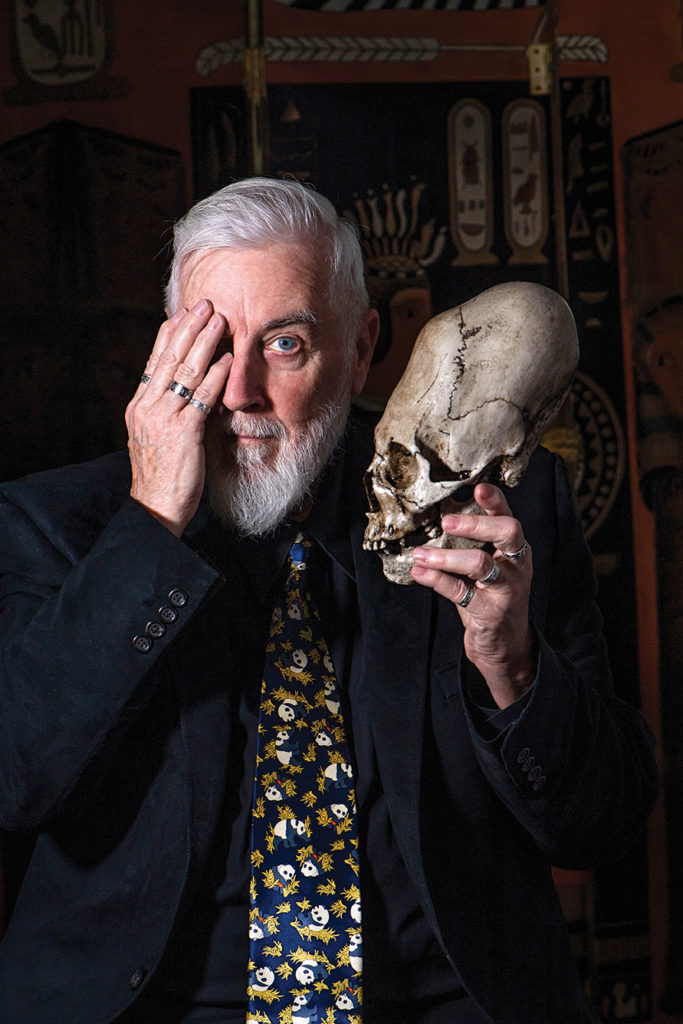

Loren Coleman and the Radical Field of Cryptozoology

How a young boy with an inquisitive mind grew up to become an author, museum director, and professional Bigfoot hunter.

Meet Loren Coleman, executive director of the world’s only International Cryptozoology Museum, which he founded in Portland in 2003. He is known as the world’s most popular living cryptozoologist—cryptozoology being the study of hidden, unknown species that are yet to be verified in the field of zoology. Coleman has done over 60 years of boots-on-the-ground field-work tracking Bigfoot, and he also has 40 books under his belt, plus a memoir in the works. As of late, Coleman has been pursuing a new adventure: this time in Bangor, it’s an even bigger museum and bookstore that will also be a home for his archive of over 100,000 books on natural history, UFOlogy, parapsychology, and cryptozoology. I talked to Coleman about a lifetime of tracking—and sometimes finding—the invisible.

How do you think people see you, and how do you want to be seen?

Most people don’t know I’m male. They hear the name “Loren” and they think I’m “Lauren.” I’m talked about online as “she,” as “her.” I have a not-real-deep voice. I present myself the way I am, which is calm, soft-spoken, and with a whole history of pacifism as a conscientious objector. I have a degree in psychiatric social work, was senior researcher at the Edmund S. Muskie School of Public Service from 1983 to 1996, and I’m a baseball dad. That’s the most important to me—a lot of my decisions have been based on where my kids are and how much time they need with me. Cryptozoology is the passion that eventually grew into my job, so to speak.

Do you believe in Bigfoot?

I believe in nothing, and I’m open-minded to everything. The evidence that I see: the tracks, the hair samples, the animals that are preyed upon—those are all the physical evidence. I don’t get into the paranormal, and I’m more into my philosophical, internal clock or network of taking information in. I don’t investigate a Bigfoot report and believe that report. Instead, I accept or deny the evidence. I really am very cautious of the two different ends of the continuum; both can be very confusing to the excluded middle that I occupy. There are people who accept everything: they hear a noise in the woods, and they think it’s a flying demon or a dragon or a Thunderbird or a Bigfoot. And on the other end, there are the debunkers, the skeptics with a big S. If someone comes along and says, “that’s foolishness,” or “those replicas that you have at the museum are toys,” it doesn’t bother me. I know why I have them: it’s to represent what they might look like and ask witnesses, “Is that near to what you saw?” I use them as measuring sticks for people to compare their experience with. I really don’t put a lot of energy into arguing with people, and I’m absolutely not evangelical about cryptozoology. Rather, my brain needs to be stimulated and filled with passion, with different stories, with different experiences. I don’t smoke. I don’t take drugs. I have cryptozoology. It’s everything I need.

I was called a radical within a radical field, and that makes me comfortable. That makes me happy.

Tell me how you were once a kid who grew up to be a professional Bigfoot hunter.

I read all the time when I was young, more than anybody else in my family. In the late 1950s, I was reading a lot of Roy Chapman Andrews. He was an explorer with the American Museum of Natural History. He went to the Gobi Desert, discovered dinosaur fossils. There was Raymond Ditmars, a herpetologist who wrote books on snakes. And of course, there was Jane Goodall. I was interested in the subject of natural history, but also the individuals who were exploring very much interested me. In March of 1960 in Decatur, Illinois, I watched a film that very much captured my imagination. It was a Japanese science fiction horror film called Half Human, or Beastman Snowman. The director was Ishirō Honda, who also did Godzilla and Rodan, and I found out he had been a documentary filmmaker for years before he got into science fiction films. I went to school the next week after seeing this movie twice and asked my teachers, “What is this?” And of course, there were no books on the Abominable Snowman. There were no, you know, cryptids. My teachers told me these creatures don’t exist, to go back to my homework, and to leave them alone. And so that of course instilled in me a desire to find out everything I could.

Let’s talk about that famous video clip of Bigfoot. What’s your take on that clip?

October 20th, 1967. That’s when the film was taken. And now, with NASA-quality computer enhancement, you can see features in the film. There’s a lot about the film that people missed in the first decade or two. Now, you can see there’s muscle movement in the back of the legs. The muscles contract. A lot of people, when they first saw that film of Bigfoot, they would say, “He did this,” or “He went that way, and he crouched over.” With more developed technology, it didn’t take too long for people looking more closely to see that this is a female. She has breasts. They move. So the most revealing of all of the hoaxes with Bigfoot is that it had been male. That’s something that I’ve documented. Bigfooters used to be male, and now it’s gender diverse, but most of the men that wrote those books could not bring themselves to talk about a female Bigfoot. They talk about males only. But I was trying to document the genders and the sexual evidence in the field, and it got me into all kinds of trouble. I shook them up. I was called gay for doing it. I was called a radical within a radical field, and that makes me comfortable. That makes me happy.

Read More:

- Milkweed Man

- A Stitch in Time

- Saltwater Classroom Uses Tech to Teach Ocean Conservation

- This Go-To Ice-Fishing Tool was Invented in Maine

- A Q&A with “Best American Essays 2022” Guest Editor Alexander Chee