Making Friends of Enemies in the Maine Woods

Making Friends of Enemies in the Maine Woods

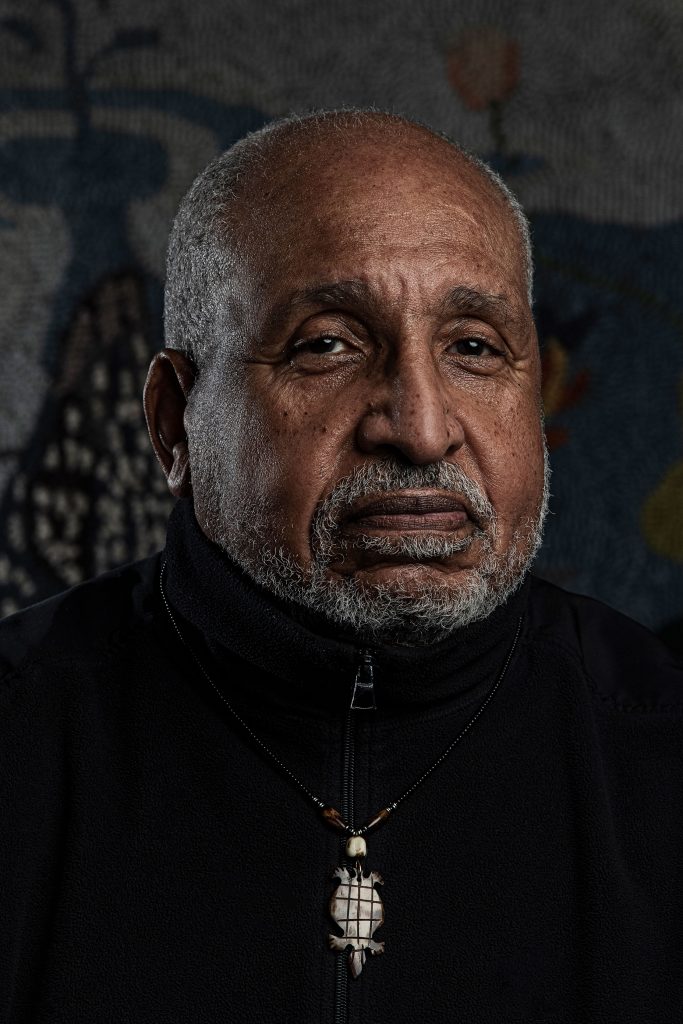

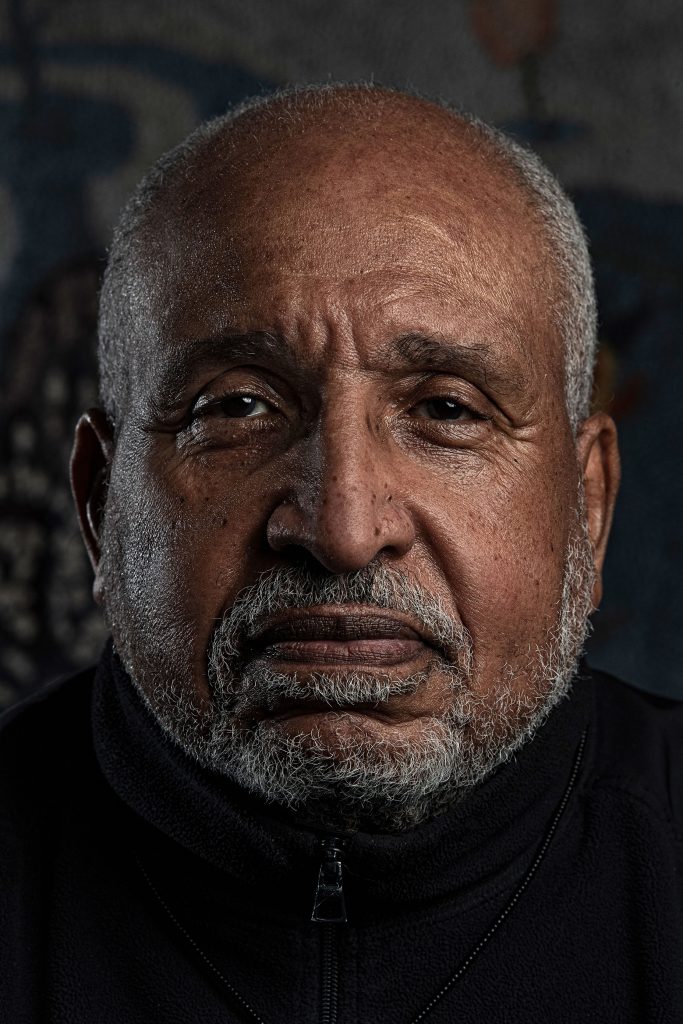

In his nearly three decades with Seeds of Peace, Timothy Wilson has worked with campers from all over the world.

by Paul Keonig

Photography by Nicole Wolf

Issue: May 2021

Timothy Wilson has been with Seeds of Peace since its founding in 1993 by John Wallach, a journalist who envisioned a summer camp that would bring teenagers from conflict zones to the United States. Located in Otisfield in western Maine, the camp has brought thousands of kids together for dialogue sessions, leadership development, and traditional summer camp activities. Wilson, a senior advisor to the organization, previously served as the director of both the Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine and the Seeds of Peace Center for Coexistence in Jerusalem. Along with his work with Seeds, Wilson had a long career as an educator and was inducted into the Maine Sports Hall of Fame in 2019 for coaching football and wrestling at the high school and college levels. He’s also been appointed by three different Maine governors for various posts, including chair of the Maine Human Rights Commission and state ombudsman.

Seeds of Peace was founded on the idea of giving a face to your enemy. So, when you’re working with kids from opposite sides of a conflict, like Israeli–Palestine, how do you facilitate conversations between people who could be considered enemies?

The biggest thing is creating a setting where they feel safe to talk.

And how do you do that?

They know that what they say stays inside that area. It’s trust, communication, and respect. You have to listen, and you have to trust what you’re going to communicate is going to be respected. It’s like a stool. If you don’t have one of those [supports], the stool falls down. And that sounds simple, but that’s the way it works. One of the biggest things I learned is each one is going to try to talk to the other one about their pain. Once you can get past that, then you can really begin to have a reasonable conversation about their feelings, the things that they hope for, the things that they respect. But there’s always going to be something in the way because of what the adults have already created. And some things you can’t change. You can’t change that the Israeli kids, 95 percent of them, are going to go to the Israeli army. That’s the problem when you talk to the Palestinians. Always will be a problem. But when the kid or when the person comes back from the military, it’s how they then still try to relate to the Palestinians. There are some pretty heavy issues when you have discussions about what they see in the other person. It’s that human part. As John [Wallach] would say, “That person has a face.”

Is the process successful?

Yes. Sometimes not as much as you want, but there are successes. Some of the people that started out in 1993, ’94, ’95, ’96, those early ones, they still talk to the Palestinians who were with them at that time. They still have conversations. They still check on each other. But the point is, until the governments allow certain things to occur, the people aren’t going to be able to move in a direction that might be beneficial.

Is it ever discouraging to see the larger conflicts between groups like Israel and Palestine not change or not improve over time?

I don’t see it that way because I deal with small pieces—small but big to me. The young people, I see them still working to do certain things, still trying, still hoping. That’s the part I deal with. I don’t make the laws or policies for that part of the world.

What role do traditional summer camp activities play in the program and in developing relationships between campers?

What happens is you have a group you sleep with, a group you eat with, a group you go to dialogue with— they’re all different. So, when you get on the playing fields, it’s another group. That’s the way you get to know everybody in camp. We would have a sports day, and we would participate against other camps. The classic example is when we were playing Takajo Camp in soccer. It was a tie game, and one of the kids, the goalie, saved it, threw it out, and they started up the field, dribbling up the field and crossing it. And then a Palestinian crossed it, went back to an Israeli, back to the Palestinian, and he scored. That answer your question?

Yeah, I think so.

We also have something at the end of every camp. There is a color game, and you split the camp in half. I’ve always said that was a way to gauge whether we had a successful session. At the end, they’re lined up on the beach and you read out all the scores. The team that wins gets to go in the water first. You’ve never seen anything like it. There’s no way to describe it. You got kids from Israel, kids from Palestine, hugging each other, jumping up and down in the water because they just did something together. Whether it was doing the rope, whether it was singing something in their camp song that they created, whether it was a chess match, everybody gets to compete at something. If you ask a kid, whether [they participated] in 1973 or 2019, the way they equate themselves, it’s “What team were you? You blue, or you a green?” If I go back and I ask some kid from 2000 or whatever, “What team were you on?” they will tell me chapter and verse, because that was our special thing. It’s the report card of the summer.