Land Rover Defender

By Chelsea Holden Baker

Photographs by Scott Peterman

Mike Smith’s name is as anonymous as the taupe warehouse in Rockland’s Industrial Park where his company, East Coast Rover, quietly custom-builds and restores Land Rovers to better-than-new condition.

As you drive north on Route 90 in Warren, Maine, there’s a clearing on a rise to the left. At 50 miles an hour the field of boxy shapes and sun-baked colors might evoke Anglophilia, African safaris, Italian police, Fidel Castro, the Paris-Dakar Rally, the UN of another era, or the International Red Cross of today. Nearly twenty vintage Land Rovers, from Series-styles to Defenders and a Range Rover, are lined up in front of a hoary warehouse and attached barn. There is no sign, and business does not look good.

“When I go out to dinner in Rockland and it comes up that I own East Coast Rover, people say, ‘Oh, we’re so sorry to hear you went out of business!’” says Mike Smith with a wry smile. “I say, ‘What are you talking about?’ and they tell me the shop looks deserted. I tell them that that shop is deserted because we moved to a place five times as big and just use the Warren shop for spare parts, frame —things that take up a lot of space. Then they say, ‘So, you can make a living from Land Rovers?’” Smith pushes up the sleeves of his gray East Coast Rover (ECR) sweatshirt as he relays this story from inside the new 10,000-square-foot facility in Rockland’s Industrial Park. Smith looks like a younger brother of Bill Murray. His blue eyes twinkle in a merry Murray-way when he talks about how off-the-radar his custom-build and restoration shop is: “Maine’s sort of famous for that. There’s these little niche, pocket businesses—like CedarWorks that makes playsets or Back Cove Yachts across the street—that operate out of Maine because they can get the people, the craftsmen, to do that kind of thing. But they don’t necessarily rely on Maine customers.” Instead, they have a national following.

On this day, the Land Rovers inside the shop have plates from Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington, and Virginia. In the lot outside, where nearly thirty vehicles await work, plenty have Maine plates, but the most exotic one is from Hawaii. The taupe Series’s windshield is tagged with proof that it flew through Los Angeles: a black-on-white sticker reads, LAX.

These cars have taken trips that would be taxing and expensive for a human traveler, let alone an automobile. It’s not that you can’t

have Land Rovers restored or customized elsewhere; it’s that the seven person team at ECR has built a reputation, bolt by rust-proofed, perfectly aligned bolt.

“When you look under the hood of a Rover they’ve worked on, you’ll find small dots of paint between parts, like between a bolthead and an engine part,” says Jeff Aronson, a Vinalhaven resident, the owner of two Series vehicles and the long-time editor of Rovers Magazine. “As long as the paint dots remain lined up, you know at a glance that the bolt or screw has not moved. That means nothing is leaking or loose. Race car shops do this routinely, but I’ve never seen that at a Land Rover dealer or a local mechanic—no matter how good they are.”

Esteem in ECR’s work can be summed up by a sticker. Defender 110s are rare cars in the United States. Only 500 of them were imported, and like the works of art that their owners contend they are, each is numbered as part of the series. Occasionally, a Defender 110 or, more often, a Defender 90 (of which there are fewer than 7,000) goes up for sale on eBay. In recent years trucks have been listed, “restored by ECR,” showing the hunter green ECR sticker on the back, where the shop brands vehicles they’ve worked on. Except, Smith says, ECR has never seen some of these trucks. Stickers the tiny Maine company had given away at events like the Land Rover National Rally in Utah and Colorado were being used as a sales tool. The three letters ECR increase the value of the car—or at least its cachet.

THE BUILD-UP

Smith says, “If you’ve heard the word Defender, then you’ve probably heard of us,” but it doesn’t sound like braggadocio. When Smith speaks, it’s with the calm assurance of a master craftsman. Growing up in Camden, he was the kind of kid who would dismantle his bicycle just to put it back together. Smith also had a role model in details: his dad is an artist with an interest in cars, including his old Land Rover Series IIA, a truck that was imprinted on the American consciousness by the popular 1966 movie Born Free. Smith went on to study film production at Rochester Institute of Technology. When he graduated he moved to Los Angeles and worked in film for a time, but his sister was working on yachts in the Caribbean, and that seemed like fun. He got his captain’s license.

Doing restoration work on megayachts—100-to 150-footers—took him around the world. On the job in Japan, Smith met Debbie Roe, a woman from England who later became his wife. Eventually they found themselves in Florida with a grass-is-greener feeling. He wanted a dog. She wanted a horse. The question was: What would they do on dry land? Driving down U.S. 1 in a Toyota 4×4, a Land Rover Series IIA wagon went by. Smith said, “I’ve always wanted one of those.”

To a British woman, that hardly seemed like a pipe dream. The trucks are all over the U.K. and significantly cheaper than in the United States. In 1993, the couple paid a visit to her parents, imported a few old Series vehicles to Maine, and Smith got to work in his parents’ driveway in Camden. Soon Smith moved the outfit to a friend’s garage in Hope and word spread that they had built up an inventory of vintage Land Rovers. Soon they didn’t have to seek out work.

The production designer for Ace Ventura Two: Nature Calls called ECR. The movie was filming in South Carolina, but the story was set in Africa and the production needed a few good-looking Land Rovers for authenticity. Smith agreed to supply them, so they upped the order to 12—due in two weeks. Smith says, “Because I worked in the movies in California, I knew that if you wanted the job, you had to say, ‘Yes,’ when the production designer asks.” Saying yes allowed ECR to move inventory that didn’t meet their specifications and start afresh, doing restorations the ECR way, with capital in their coffers.

The team Smith assembled to fulfill that order (and several more for movies and commercials) turned a small operation into a team. The crew came mostly from guys he knew through boats: “We knew that they had skills—from welding to painting—and somebody always knew somebody.” From the beginning, ECR made a concerted effort to keep everything in the building.

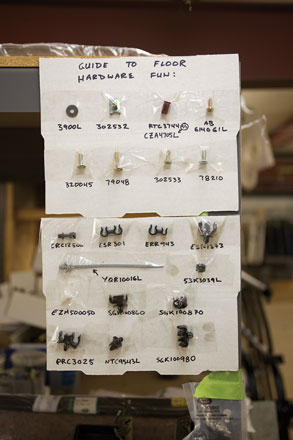

Fifteen years later, the only thing that’s ever farmed out is soft upholstery work. ECR fabricates dashboards, doors, sound systems, and seats. They have kept original jigs in use at British parts manufacturers by taking on distribution of items like roll cages when Land Rover itself discontinued the line. The ECR “parts library” has thousands of items—nearly every piece of a Land Rover that you could ever need.

Smith says, “If I was smart, we’d be somewhere more central, but I grew up here, and it’s just that sort of New England boatbuilding mentality that we’re going for.” The emphasis on craftsmanship combined with engineering and in-house workflow is what has made ECR much more than a mechanic’s shop and compels customers to seek them out, even in a remote region of the country. “Mike took his engineering background and production systems management approach from yacht building and applied it to Land Rover work,” says Aronson. “To me, ECR is the Beal or Duffy lobster boat, the Hinckley Yacht, of the Land Rover world.”

ECR customers include a couple that toured the world in their Land Rover by shipping it from one continent to another, writers, Major League Baseball players, photographers, car collectors (like a man whose stable includes tanks), and twenty-somethings who grew up coveting a Defender and worked their way there.

Their reasons for purchasing the vehicles vary widely, but Smith says a unique thing about Land Rover lovers is that, no matter their backgrounds, they always seem to get along with each other and the shop. As for customer relations: Smith was so overwhelmed by phone calls every two minutes that he hired an office manager, Holly Le Royer, and now speaks with people after work has begun. Smith says, “I live a sheltered life. Holly always says, ‘Do you know who that is?’ and shows me their websites. Up until then they’re just ‘Matt’ or whoever to me. And maybe that helps with our contact, because it’s just me and them, without the Hollywood fear factor.”

THE DREAM

ECR’s tag line is: “Our only limitation is your imagination.” The team recently built a “Game Viewer”—a Defender 110 safari car with stadium seating for nine—based on a photo from Africa. The truck is now used to watch lions, gazelles, and zebra—on a Texas ranch. Several years ago, an enthusiast sent in a Photoshopped image of a soft-top Defender 110—a car the factory never made, but ECR did. Copley Motorcars in Massachusetts—which specializes in unique hard-to-find vehichles—financed the build, and the truck sold before ECR finished it. Smith dubbed it “The Beachrunner,” after a toy he had as a kid. The shop is now at work on the fifth model. Apparently, the passion for Defenders has not been quelled by a bad economy: ECR’s waitlist is over two years long.

Smith drives a Discovery to ECR, but he’s been working on a Defender for himself—customer cars just keep pushing it out of the shop. He is also restoring an Amphicar (amphibious car) and still spends time on the water—in a boat—in the summer. With the birth of his son six years ago, Smith has scaled back on his past life of out-and-back off-roading to remote areas of Mexico and Labrador where cars must carry their own jerry cans. Instead, he and his wife meet up with his British in-laws in Florida. But he’s making a living doing what he loves, on dry land, back at home with his family, which now includes a dog—and a horse.

East Coast Rover Co. | eastcoastrover.com