A World Apart

FEATURE- July 2011

By Isaac Kestenbaum

Photographs by Jonathan Laurence

Growing up at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts.

At first, I thought Haystack looked like something from another planet. specifically, to my eight-year-old self, it seemed exactly like the Ewok village from return of The Jedi. The tribe of small, furry, bearlike ewoks lived in huts built high among the trees, their homes connected by walkways.

The Haystack Mountain School of Crafts is similarly suspended between the ground and the sky, a floating village of cabins and studios connected to one another by boardwalks. The school is perched at the edge of the sea, at the end of the Sunshine peninsula on Deer Isle, which itself feels like it’s perched on the edge of the planet—or, when you’re a young boy, some alien planet of your imagination.

Haystack takes its name from Haystack Mountain in Montville, where the school was founded in 1950 and where it resided for 11 years. When Route 1 invaded, the school moved to its present location, a place where no highway would ever dare to go. My father, Stuart Kestenbaum, is nearly as old as Haystack, and in 1988 he became its third director, moving our family from Portland to Deer Isle when he took the job.

When I’m asked to describe Haystack, after first comparing it to an Ewok village, I’ll likely say that it’s one of the most beautiful places on earth, and the temporary home for a revolving community of artists, craftspeople, and thinkers who, each summer, come from all over to stay at Haystack’s cabins, eat in its dining hall, and work for two weeks in its studios. This transient population of creators and thinkers also take classes in—to name only a few of the school’s many offerings—ceramics, glassblowing, jewelry making, woodworking, weaving, blacksmithing, bookbinding, and printmaking.

I know Haystack from the ground up—literally. My younger brother, Sam, and I spent many summer days hunting for treasures underneath the school’s decks and walkways. Once, a student lost an earring, and we were tasked with finding it. I remember feeling proud of the commission—I was a specialist, the only one equipped for this dangerous task, a dirty-kneed explorer of an underworld known only to me.

Sam and I were drawn to the hidden corners of the campus, such as the secret walkway beneath the drawing studio and the crevasses between rocks on the shore. The forest was especially enchanting, filled with ragged, asymmetrical spruce and fir trees that swayed in the ocean breeze. In one area of the woods, I found a giant pillow of moss that was as big as I was. I would sink my hand deep into it, and my handprint would remain while it slowly exhaled and swelled as it regained its natural form. Elsewhere, the landscape repeated itself in miniature: patchwork carpets of moss and ankle-high saplings became tiny forests and fields, each perhaps containing its own miniscule replicas within, without end, like a fractal.

Boulders fill the forest around the school, leftovers from the last ice age, but to me they were moons and asteroids orbiting planet Haystack. I would climb the highest ones and observe campus life unfolding beneath me. Some boulders even had full- grown trees on top, surviving, incredibly, on meager patches of wind-blown soil. The entire campus sat upon a thin layer of topsoil, and when a tree fell it pulled up a disc of roots and spruce needles only a few inches thick, revealing the hard bone of Maine granite beneath the skin of the earth. Sam and I also explored the school’s studios, mesmerized by the students in the “hot shop,” who flung molten glass around like glowing honey, intrigued by the hushed concentration in the drawing studios, or curious about the sound of machinery and dust from the woodshop. The students likewise fascinated us, and it was through Haystack that we first met people from other countries and cultures.

But to me, the soul of Haystack always was—and still is—my father. He would stride up and down the stairs with a ring of keys hanging from his belt, a jingling sound that announced his arrival and, to his sons at least, signified his authority and importance. He seemed to know everything about the school, even the number of steps that compose the main staircase and form the central artery of Haystack. I won’t reveal the figure here because my dad often likes to make visitors guess it.

My first real job was in the Haystack kitchen, chopping vegetables and making salads for the sprawling, family-style dinners. I operated the mechanical dishwasher and rang the towering dinner bell three times a day to summon the students to eat. The breakfast shift in the kitchen began at six o’clock in the morning, and even in the height of summer the Maine air can be brisk at that hour. To this day, the smell of breakfast cooking in the cold air will instantly transport me back to those quiet summer mornings of my adolescence.

I often worked the Fourth of July dinner shift. It would just be getting dark when I finished work, and once, I climbed onto the pitched roof of the dining hall, along with a few other workers and students, in the hopes of catching a glimpse of fireworks. At the edge of the horizon, across the bay, we could barely make out the varicolored explosions in nearby Stonington—so tiny, like galaxies colliding in another universe.

There’s an ancient Greek paradox about the ship of Theseus: after many adventures and repairs, every plank and piece of lumber on the ship eventually had been replaced.

The philosophical question: Is it still the same ship? I often recall the paradox at the start of every Haystack season, when the springtime repairs are made to the campus, and new, bright-yellow boards appear in the decks and new shingles appear on the buildings, standing in stark contrast to the weathered wood. Haystack is a lot like the ship of Theseus—always the same, but always different, changing from season to season.

Although Haystack seems like it sprung, fully formed, from the land on which it sits, it was actually designed by the architect Edward Larrabee Barnes, who also designed skyscrapers in New York City. Built in 1961, Haystack is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Traces of its original features abound. The ceilings of some cabins still hold footprints from the construction crew, preserved in pitch. And hidden in plain sight between the parking lot and the glass studio sits a small shack that the construction crew originally built to store the architectural blueprints in. Never intended to be a permanent structure, it has somehow avoided destruction over the past half-century.

Today, a Haystack employee, artist, and good friend of the family—not to mention an excellent chef—has turned the shack into a sort of experimental kitchen, making sourdough and scones, and delicious steaks and lobster rolls. I’m not going to name him here, since he values his privacy, but if you’ve been to Haystack you know whom I mean. (This same man once famously rode his bicycle down the main stairs.) Virtually all of my family friends work at Haystack or are otherwise connected to the place. The first director of Haystack, the late Francis Merritt, and his late wife, Priscilla—two of the kindest people I’ve ever known—lived across the street from us when I was younger. In both small and profound ways, my family life is inextricably entwined with Haystack.

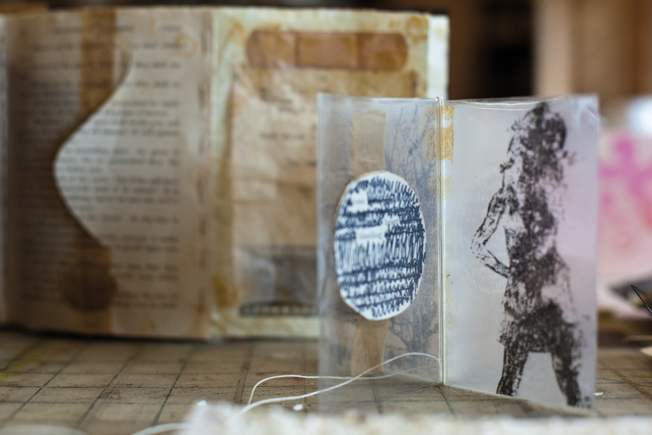

When I was younger, my family spent long afternoons on Haystack’s one small beach, which is made entirely out of crushed shells. As I grew older, these days became less frequent, but the four of us still converged on campus often. Once, my mother, Susan Webster—an amazing artist and printmaker— was teaching a session. My brother was hanging around, having somehow fallen under the tutelage of the ceramics teacher; as I recall, he was creating a samurai elf out of clay. My father was there, of course—he was almost always there. I had spent the day on campus, but I had plans elsewhere that evening and left shortly before dinner. Yet as I drove over the causeway—a thin, winding strip of road that connects the peninsula to the mainland—something made me pull to the side of the road near the ocean. The light was soft and gentle, the late-summer sun was low in the sky, and the whole world seemed to be glowing from within. I realized in this moment that there was nowhere else I wanted to be. I returned to Haystack and to my family—the two words almost synonymous.

Somehow I managed never to take a class at Haystack until I was an adult and no longer living on Deer Isle. I had been part of a few weekend workshops, but never a full two-week session.

So when I had a couple months between jobs, I enrolled in a bookbinding course.

My previous job had been in an office, and after endless days in a cubicle, Haystack, once again, felt like another world, a fantastical escape, an Ewok village. Over the course of the session, time seemed to warp—two weeks passed like a few moments, but each moment expanded to encompass many experiences. I stayed up well past my office-life bedtime working in the studio. I made new friends from all over the world. I ate, I slept, and I made art.

Lots of people talk about the “Haystack experience,” but before I took a class there I never fully understood what it meant. It turns out that Haystack is a real part of planet Earth after all, and that it couldn’t exist without the staff, teachers, students, and the town of Deer Isle. It can still take you to another world, but it’s a world that ultimately exists inside of you.