Claiming Space at the Table

Tender Table, a collaborative of BIPOC storytellers, blazes a trail for the vibrant and diverse communities of Maine.

Stacey Tran realizes it can be difficult to find a sense of belonging when your culture isn’t reflected in the place where you live. For this writer (I am half Chinese and based in Portland), that notion hits close to home. In Maine a staggering 94.2 percent identify as “white alone,” according to census.gov. However, that still leaves over 100,000 people living in Vacationland from other origins and ancestry.

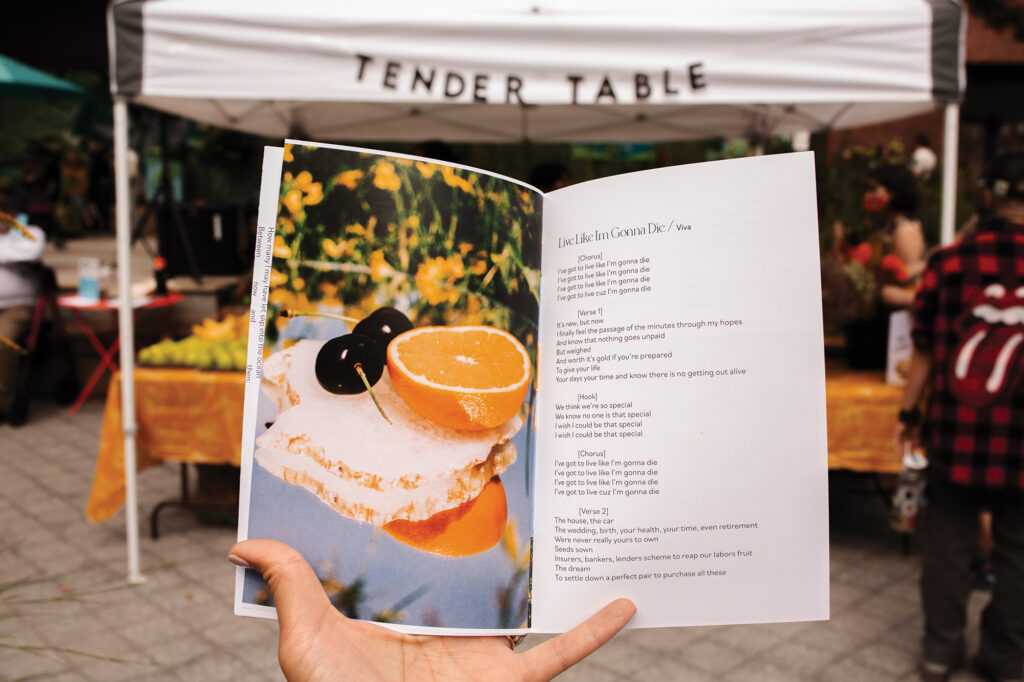

This made me wonder: What do I need to feel safe, heard, and supported? What kind of setting makes me feel most open, most connected to my community? Enter Tender Table, a community-centric, volunteer-run organization that celebrates Mainers of color through food and storytelling. Events vary, from picnics and poetry readings in public parks to virtual book clubs, artist talks, and dinner parties. The content might shift from one event to the next, but the mission stays the same.

“There are so many spaces in the world where people of color feel like they can’t let their guard down,” Tran tells me. “Their identity, their existence, is constantly in question. So, we’re making that space.” To date, just over half of Tender Table’s events are for people who identify as BIPOC only, with the others open to everyone.

“For so many of us, we already have to hand-hold people through race on a daily basis,” says co-organizer Veronica Perez. “Or be that person who represents an entire culture at work or school. Here, it’s sometimes nice to just sit back and ease into conversations that we know won’t be filled with stereotype.”

Perez is a multidisciplinary artist who has received fellowships at Indigo Arts Alliance’s David C. Driskell Black Seed Studio and the Lunder Institute at the Colby College Museum of Art. Despite their success in the Maine arts community, Perez, who is half-Puerto Rican and Italian, almost left Maine at one point, due to an unhealthy work environment that left them feeling isolated. In one of many instances, Perez felt gaslit by colleagues and was told they were overreacting when they finally confronted issues. I nod when Perez tells me this, recognizing these behaviors in many interactions I’ve had throughout my own life. Often, discussions about race with family and friends result in scenarios where people of color end up doing a lot of the heavy lifting.

“It’s not [a BIPOC person’s] job to educate,” Perez says, adding that there are resources available now for those who want to learn about how embedded racism is in our belief systems. Tender Table is a place where you don’t have to worry about any of that, where, Perez adds, “you can loosen your jaw and stop clenching.”

Tran recognizes that, to reduce this tension, sometimes being around those who have been in similar situations is a great relief. “At our events, you can expect to be among others with shared and overlapping experiences and cultural backgrounds. They are centered around themes of healing, joy, rest, and connection, with food as the binding element.” Tender Table member Jenny Ibsen is a Chinese adoptee who grew up in a white family in Connecticut. Now she’s a printmaker, illustrator, and writer living in Portland, who advocates for restaurant workers. “There was a group of other Chinese adoptees who were all born in the same city as me, that I spent time with once a year. We shared stories of our adoptions and our families, bias incidents that we experienced (but barely understood in elementary school), and curiosities about our birth parents. We didn’t always talk about heavier topics—we laughed, watched TV, went swimming, and jumped on trampolines. But there was always an assumption of a shared experience, an openness that I could rarely find with my classmates or my parents, who would talk with me but could never empathize.” For Ibsen, Tender Table fills the same void.

“Tender Table isn’t just a place for us to rant, although it can be that for someone if they need it,” Tran says. “In one meeting I felt the group’s exhaustion when talking about race. What about food? Bad TV shows? Nature trails?” She tells me there was a collective sigh in the group. I wonder how many fellow Mainers are searching for this release but don’t even know it. “So much of our progress and events have happened because of conversations with one another and our communities,” Tran says. “Not because Tender Table is bound by some expectation. We listen, we see how the community responds, and we make things happen in response to that.”

This approach is opposite to the five-year busi-ness plan many organizations are modeled after. Instead, Tender Table operates as a call-and-response with their attendees. It asks itself and its communities: Is this going to help us build more relationships? Is this going to lead to deepening connections, to people doing amazing things? Can we support them? Can we support you? This meant that for the majority of 2020 and 2021 meetings were held over Zoom, to ensure that the community stayed safe and yet connected during the pandemic. In one memorable meeting, Tran delivered ingredients for making soup to each attendee’s front door, and they cooked together remotely while bonding over recipes and stories.

Tran, whose parents grew up in Vietnam, says her deep sense of belonging began at the dinner table, and Tender Table is an extension of wanting to share that powerful, sacred space. “Through the food I ate and the stories I heard at the dinner table, I learned more about my family, my ancestors’ food traditions, the landscape they grew up in, their experience of scraping by in times of poverty and scarcity, and the delicious nostalgia of very special decadent meals at New Year celebrations complete with firecrackers and the whole neighborhood singing karaoke into the wee hours of the morning.”

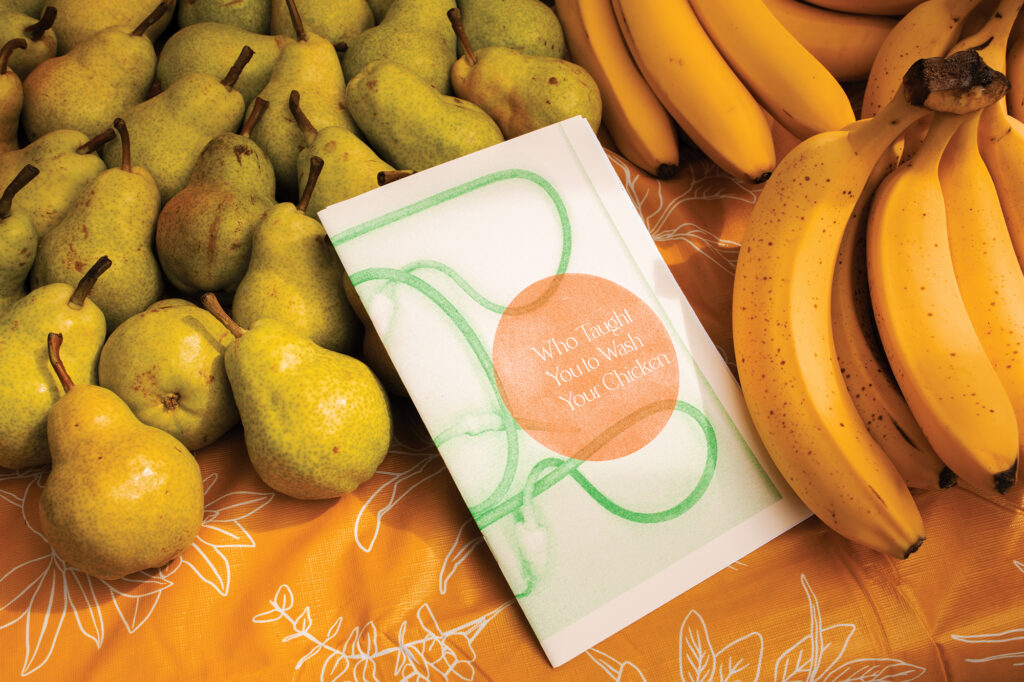

Perez knows that not all tables are that generous. “My family had evening dinners, but they weren’t always generative and kind. I sometimes left the dinner table in tears. It’s who you surround yourself with at the dinner table that creates spaces of vulnerability, and that is what Tender Table does.” Now, at the Tender Table helm with both Tran and Ibsen, who was asked to join the team as an artistic collaborator and organizer, Perez has no intention of leaving Maine. Tran also invited Sydney Avitia-Jacques, the political education director at Southern Maine Workers’ Center (SMWC), to join the growing Table, and now these four organizers have big plans for the year ahead. Tender Table is partnering with SMWC and Indigo Arts Alliance to host several events throughout 2023 in conjunction with the appointment of renowned musician and activist Toshi Reagon as Bowdoin College’s 2022/2023 Joseph McKeen Visiting Fellow. Reagon has invited members of the Maine community to create cultural and social justice programming based on themes from Octavia Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower. The programming will accompany Reagon’s Parable of the Sower opera, which is on tour and will be performed in April 2023 at Merrill Auditorium. Tender Table will create a series of workshops and dinners to hold space for community skill sharing and conversation.

Later this year, Tender Table plans on bringing back a version of its successful (and really fun) annual food, poetry, and art fair. For the past two summers, this vibrant event brought the BIPOC community to center stage, under the canopy of trees and tents at Congress Square Park. Tran says this year will be similar: tables filled with food and music and tents adorned with goods and art crafted by Mainers of color. After attending the past two Tender Table fairs, I can attest to how energizing it is to see a group clearing some space so that artists can fill our state with the diversity we already have as well as with the diversity to come.

“The world begins and ends at a kitchen table,” Tran quotes from her favorite poem, “Perhaps the World Ends Here,” by Joy Harjo. “No matter what, we must eat to live. The gifts of the earth are brought and prepared, set on the table.”

Tran ends with a big smile, an invitation, and perhaps a challenge. “We welcome your hungry and curious selves and hope you’ll leave feeling nourished and restored.”

From the Community

Florence S. Edwards, dentist and podcaster

“Tender Table provides a space where I do not feel othered. I can let my defenses down and not be exposed to micro-aggressions. It’s a very affirming feeling, to be surrounded by people who know and can relate to the challenges I face.”

Ashley Page, studio and programs coordinator at Indigo Arts Alliance

“Tender Table is an inclusive (sometimes even virtual) gathering centered around food, community, and storytelling that allows for BIPOC folks to spend time together and forge new links between food and culture.”

Hoi Ning Ngai, associate director for employer engagement & business advising at Bates Center for Purposeful Work

“I don’t often experience really thoughtful listening in a way that prompts connection, and I’m always grateful that Tender Table events allow me to be as engaged as I want to be, without pressure to share more than I’m ready to share. I feel safe.”

Read More:

- Claiming Space at the Table

- How to Keep Your Houseplants Alive This Winter

- How to Winter in Maine

- 9 Creative Craft Coffees to Mix Up Your Morning

- Timeless Appeal at Portland’s Swiss Time